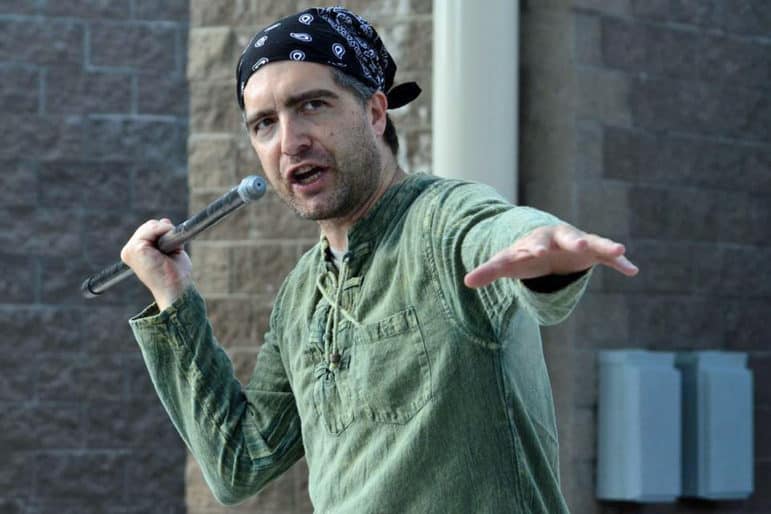

Matt Robinson

Algernon D’Ammassa

COMMENTARY: To the Honorable Paul Davis Ryan Jr., Speaker of the United States House of Representatives;

Dear Mr. Speaker,

Today I write in humble nomination of myself for the recently vacated position of Chaplain for the U.S. House of Representatives. An unusual candidate, I write to persuade you I am the right choice for a peculiar time.

As the first Zen Buddhist chaplain to serve Congress, my appointment would be an historic gesture of inclusion during your closing days as speaker. However, regardless of my faith tradition, here is the main reason I am the right candidate: I have no intention, whatsoever, of showing up for work.

You read that right, Mr. Speaker: if hired, I will refuse to serve.

In fact, I will not even set foot in Washington. (Dreadful place, nothing would entice me.) If a member of Congress desires to meet with me, they can mimic the supplicants of Zen lore and come to the desert to find me.

Every Congress has had their House and Senate chaplains, opening legislative sessions with prayers for heavenly guidance unto these rascals who nevertheless shame their Creator, waging one war after another, leaving the poor in the dust, piling ash on the needy, and bowing to wealthy donors and foreign tyrants.

Of what use, then, is a chaplain? It is necessary neither for genuine pastoral care nor pro forma displays of piety. The House floor is mostly empty for the morning prayer. Compared to 1789, members of Congress can easily travel to their home districts, where they may be photographed alongside the pastors whose advice they ignore and be seen bearing election-season witness to local congregations.

A few weeks ago here in New Mexico, the Doña Ana County commission voted to invite area faith organizations to offer prayers before their public meetings. Chairman Ben Rawson said such prayers “seek peace for the nation, wisdom for its lawmakers, and justice for its people, thus appealing to universal values embodied not only in religious traditions but also in our founding documents and laws.”

This summoned, with requisite tenderness, the memory of Benjamin Franklin, he who recommended daily prayer to the Constitutional Convention when it was “groping, as it were, in the dark, to find Political Truth.”

Franklin was a deist who believed a Christian framing would influence legislators toward virtue, as it would the rest of society. It was the belief of many in his generation – and, I suspect, of the first five presidents – that doctrinal belief and religious identity were less important than contributing to a beneficent and enlightened society.

Franklin believed in Providence until his final breath, yet what reading of history can testify to the benevolent influence of faith on domestic or, most certainly, foreign policy? Yet in memoriam to Franklin’s belief in the improvability of Congress, let there be a House chaplain.

With me on the job, which is to say my absence, there will be no repeat of a controversy like the Jesuit Father Patrick Conroy’s references to economic inequality and social justice. I promise not to embarrass you by calling on your colleagues to challenge such inequities, and flout the will of your earthly benefactors.

That would be just as preposterous as me asking a predominantly Christian body to participate in a Buddhist prayer in the first place; and as one who has grown up playing along with theistic oaths at public events, I am well acquainted with the indignity.

Finally, appointing me chaplain would fit a motif of the present administration: placing agencies in the charge of people pledged to their destruction. As the State Department jettisoned diplomacy, as the Environmental Protection Agency dismissed science and deleted regulations, I believe as a matter of republican principle there should be no congressional chaplain.

On this point I stand with James Madison. The fourth president called the provision of congressional chaplains “a palpable violation of equal rights, as well as of Constitutional principles.”

In 1820, Madison wrote, “The Constitution of the U.S. forbids every thing like an establishment of a national religion. The law appointing chaplains establishes a religious worship for the national representatives, to be performed by Ministers of religion, elected by a majority of them; and these are to be paid out of the national taxes.”

This, Madison called an establishment of religion “for the Constituent as well as of the representative Body,” and he was against it on First Amendment grounds.

This chaplaincy, I would argue on the same grounds, should be abolished, but I know this will not happen; and what I am learning from the current president is that the way to destroy an institution is to get inside it and hollow it out from within.

Thus, I hope you will give my application serious consideration. I will require no travel funds, no expensive modifications for my office (as I will never see it), and a modest salary befitting this sinecure.

Your most humble and obedient servant,

Desert Sage

Algernon D’Ammassa is a reporter and columnist for the Deming Headlight. He also collaborates with Las Cruces musician Randy Granger, performing stories based on Greek and Asian mythology and indigenous American lore. Agree with his opinion? Disagree? NMPolitics.net welcomes your views. Learn about submitting your own commentary here.