Adria Malcolm / for Searchlight New Mexico

John Arthur Smith in the State Capitol in late 2017.

The car tire blew. The 1948 Ford sedan rolled off the highway from Columbus, throwing the 16-year-old driver nearly to his death.

For eight years, he lay comatose in the Deming house where Sen. John Arthur Smith — today, arguably the most powerful man in the New Mexico Legislature — grew up.

James “Jimmy” Franklin Smith was a star athlete and John Arthur’s big brother. The accident on March 30, 1952 shattered his cerebral cortex, the part of the brain that’s responsible for thinking and language. The family poured all its earnings from a small liquor store into paying for around-the-clock nursing care.

John Arthur Smith, the youngest, was 11 when it happened.

Smith recalls his reaction, speaking in the third person before catching himself: “The response on how you act — my parents had enough worries without a kid getting in trouble. And it wasn’t that I was a goody two-shoes, so to speak, but the bottom line was I didn’t get in trouble.

“We were always hurting for money,” he adds. “I always had a job.”

It’s always there, in the back of his mind, the specter of the unlikely or unthinkable occurrence. Plan for the worst. Save for the rainy day. You just never know.

The family tragedy shaped Smith’s boyhood and set in motion a personal mantra that would inform every decision he makes as chairman as the powerful Senate Finance Committee: “You better be damn careful with the dollar [because] you never know what’s going to happen.”

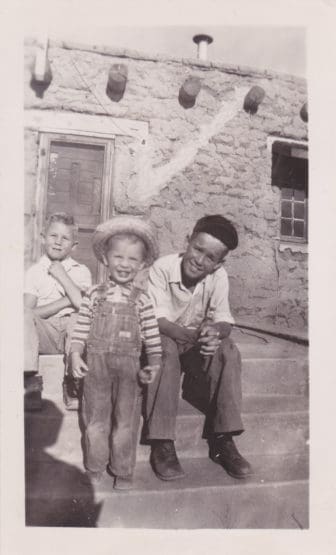

Courtesy photo

John Arthur Smith, center, as a child with his two older brothers. Jimmy Smith sits on the left; the eldest, Benny Ray, is on the right.

It became his campaign slogan in 1988 when he first ran for state Senate: “John Arthur Smith: I’m careful with your dollar.”

And then there was another tragic reminder: In 1987, after Smith and his brother-in-law opened an auto parts store, a bolt of lightning killed his new business partner. Dick Strand was riding his motorcycle home to Deming from Silver City after a storm when the tragedy struck. He was a week shy of his 40th birthday. It was the year before Smith’s first run for office.

Smith, now 76, is a fiscally conservative southern New Mexico Democrat, a real estate appraiser by trade who has served in the Legislature nearly 30 years — a decade as Senate Finance Committee chairman — and has earned a reputation as the state’s banker.

He is often called “a legend,” “hard-nosed,” and “the adult in the room when it comes to the budget.” He has earned the nickname “Dr. No.”

To some, he is the quintessential steward of New Mexico’s financial well-being. To others — especially those who cite New Mexico’s dead-last ranking for child poverty — he is the primary obstacle to more substantial investment in early childhood education.

Smith “is probably the most influential legislator in the New Mexico Legislature,” says Garrey Carruthers, a former governor and the current chancellor at New Mexico State University. “He rattles my cage from time to time. I have groveled with him and lost.”

Position and power

Nothing makes it into the New Mexico state budget without getting past Smith.

He prefers that the budget rely on recurring revenue, like taxes, and is loathe to touch anything resembling a savings account. He worries about the state’s weakened bond rating and wants to build up reserves that New Mexico raided during the recession.

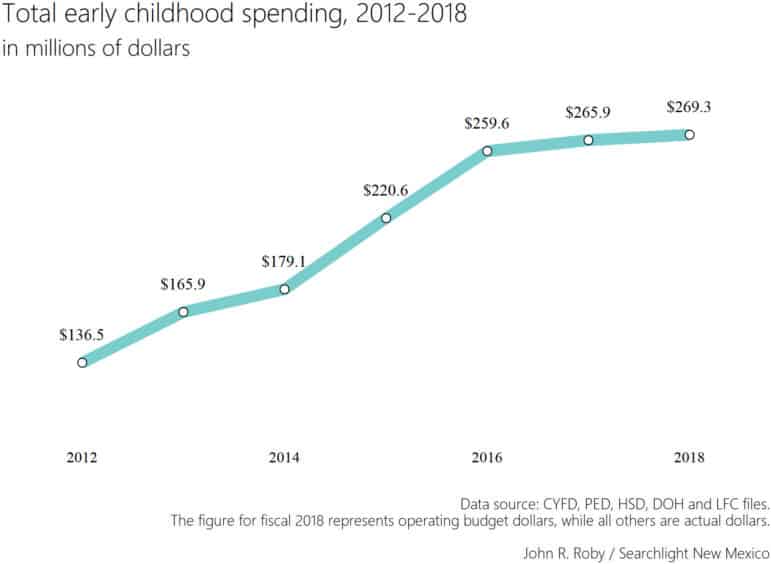

Where child well-being is concerned, he sponsored full-day kindergarten and has supported conservative year-over-year increases in funding for preschool, an extended school year program called K3-Plus, as well as home visiting — even during recent lean budget years.

But he has also been child advocates’ top foe, thanks to his opposition to proposed constitutional amendments that would take money for early childhood programs from the $22 billion permanent funds. The blessing of the Senate Finance Committee is required for a public referendum.

Such proposals often die in his committee.

People say the funds are “being saved for a rainy day,” Smith says. “They have no idea how much is spinning off right now, earmarked for education.”

Smith is both feared and widely respected. Many people interviewed for this story declined to criticize him on the record, fretting that they would have to face him at the negotiating table.

One advocate for early childhood investment requested anonymity, saying: “We understand how much power he holds at the Capitol. When it comes to talking about him, we don’t want him to backlash because of something we have done.”

Smith is the titular leader of a coalition of conservative Democrats and Republicans known in child advocacy circles as the “Smithsonians” who oppose further drawing down the funds.

Political roots

It was 1988. An ad in the Deming Headlight asked readers to “vote the Democratic ticket,” with presidential candidate Michael Dukakis at the top. A black-and-white photo showed a dark-haired Smith in thick glasses in his campaign photo for New Mexico Senate.

Smith ran a scrappy campaign against a local banker in Senate District 35, which today spans the southwest corner of Doña Ana County and all of Luna and Hidalgo counties down to the Mexican border. It is one of the state’s poorest areas, a mix of farm and ranch land and small businesses and very low wages.

He promised to take no campaign contributions and made hand-painted signs. He earned the blessing of his mentor, Ike “The Bear” Smalley, who represented the area for 32 years as a conservative Democrat in the state Senate.

Dukakis lost; Smith won.

Today, the candidate who refused to accept donations receives tens of thousands of dollars in campaign contributions annually thanks to his leadership position, with some of the biggest deposits coming from oil and gas businesses, according to campaign finance reports.

In Luna County, in the heart of the district, two-thirds of residents are Hispanic and 41 percent of children live in poverty, according to the U.S. Census and New Mexico Department of Health. Median household income is about $27,000 a year, less than two-thirds of the state’s median income of about $46,000.

The county went for Donald Trump in 2016, 48 percent versus 44 percent for Hillary Clinton. Smith won his race unopposed.

“It’s very hard to find a liberal Democrat in Luna County,” says Charles “Tink” Jackson, a former Luna County manager. “You had to be a Democrat because Democrats always won. But you couldn’t win unless you were conservative. They’re old-school Democrats there.”

Smith is a classic example. Politics, he said, “was talked around the dinner table.” His grandfather took him to see presidential candidate Harry Truman, a Democrat, when he made a stop in Albuquerque in 1948. Truman became his political idol.

“The buck stopped with Truman,” Smith says. “He took responsibility whether he succeeded or failed. That is an endangered species in politics today.”

Adria Malcolm / for Searchlight New Mexico

John Arthur Smith in the State Capitol in late 2017.

A matter of money

One November morning, Smith ambled the curved halls of the Roundhouse, looking for hot coffee in an executive office, politely putting off lobbyists from Think New Mexico, a local think tank, who had come to talk to him about reallocating dollars from public school administration to the classroom. He had a Senate Finance Committee meeting to chair in 10 minutes.

There were few big, new investments expected, as the state was still clawing its way out of the recession to restore funding that had been cut in recent years, including to public schools and universities. Lawmakers signed off last week on a $6.3 billion budget.

In committee, Smith occupies the center chair of a crescent of seats.

Agency directors come one after another explaining their wants and needs. The brightly lit auditorium is nearly empty but for the committee. Smith follows each presentation meticulously, listening as other members ask questions. And then, inevitably, he hits each presenter with the bottom line:

How do you intend to pay for it?

“There are people who don’t want to look down the road at all,” Smith says. “And I look too far. So how do I find the middle ground to make that investment?”

Given his position, the plight of New Mexico’s children has often been pinned on his shoulders.

In 2013 — the year New Mexico fell to No. 50, behind Mississippi, in the annual Annie E. Casey Foundation’s ranking of child well-being — a social justice organization called OLE showed up to an LFC meeting with a giant greeting card and a half-dozen heart- and star-shaped balloons.

“Excuse me, Sen. Smith,” said parent leader Raquel Roybal, “the people of Mississippi would like to thank you.”

In recent years, grassroots organizers have laid off targeting Smith directly — in part because it simply hasn’t worked.

An advocate from another child-focused organization said: “He is not our obstacle. Our obstacle is the entire Senate because they give him the power. I think he does mean well, but … he needs to take some responsibility for the mess New Mexico is in.”

About that, Smith says: “What’s frustrating about that is they don’t acknowledge how much has been done.”

The Legislature is already appropriating more than what agencies including the Children, Youth and Families Department can spend on early childhood, he counters.

“Spending wisely, economically and efficiently” should be the goal, he insists.

He has no plans to step aside, health and elections permitting. Smalley, the cigar-chomping senator from Deming who was Smith’s patron and mentor, served for more than three decades and didn’t quit until he was 85 years old.

“I was schooled by a good doctor that said, ‘You know, hard work has killed damn few, but lack of work has killed a lot more,’” Smith said. “My attitude is, I’m planning on working until my last day.”

Carruthers advises against laying too much credit or blame on any one elected official.

“There is a way to overcome any single state representative’s attitude on any bill,” he says. “It is a majority vote.”