Screen shot

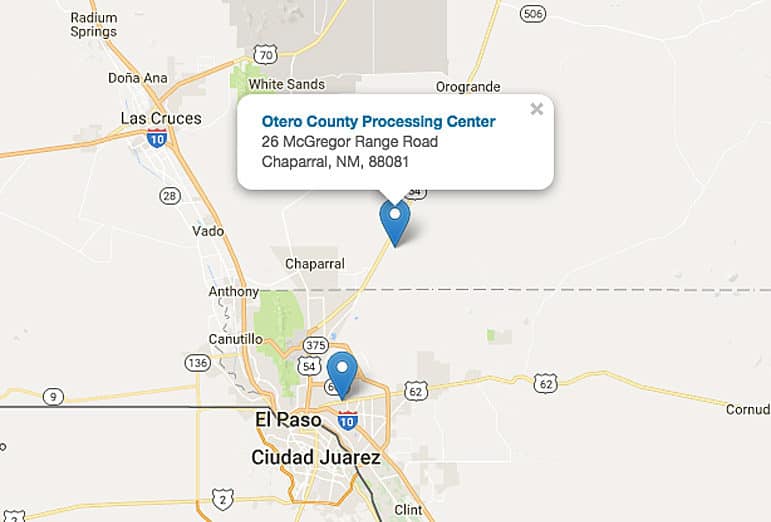

The Otero County Processing Center is located in rural New Mexico north of El Paso, Texas.

Despite its setting in a desolate stretch of the southern New Mexico desert, Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Otero County Processing Center recently landed at the center of ongoing controversy surrounding private prisons and ICE detention.

As one of five facilities audited by the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Inspector General, conditions at the remote prison have stirred debate, just as its for-profit operator, Management and Training Corporation (MTC), has moved to expand its immigrant detention business in other states.

But problems at the facility run deeper than those detailed in the Inspector General’s new report, a review of contracts and court records related to the facility’s operation found.

Meanwhile, a push to invoke more transparency of federal prisons is being made in the New Mexico State Legislature — seven years after a report by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) detailed a host of alleged abuses at Otero, and one year after an altogether different private prison contractor, CoreCivic, emerged unscathed following a scandal related to deaths in custody at its New Mexico facility in Cibola County.

The Inspector General’s recent audit found problems at four of five ICE facilities nationwide, including Otero. Discovered during surprise inspections, auditors at various sites found evidence of systematic and suspicionless strip searches, rotten food and moldy bathrooms, the misuse of segregation, the denial of communications, and long delays for medical care.

Specific to Otero, federal inspectors observed non-working telephones, unsanitary bathrooms, and unjustified lock-downs and solitary confinements.

“ICE detainees are held in civil, not criminal, custody, which is not supposed to be punitive,” the Inspector General’s office states in its Dec. 11 report. “The problems we identified undermine the protection of detainees’ rights, their humane treatment and the provision of a safe and healthy environment.”

Regional ICE spokesperson Carl Rusnok stated in an email that “ICE is confident in conditions and high standards of care at its detention facilities.” He said the agency agrees with the inspector general’s recommendation that ICE conduct reviews of areas highlighted in the report. For its part, MTC wrote that, contrary to the inspector’s findings at Otero, the facility was not in violation of standards, though the company “welcomes oversight” and is “monitored daily by ICE.”

The Otero facility has also been exempted from ICE’s usual standards for providing recreational opportunities to detainees when it comes to access to natural light and dedicated outdoor recreation, documents show.

An “intergovernmental agreement” between Otero County and ICE, provided by the county in response to a public records request, shows that the federal agency waived its standards in both regards. The contract does not require access to natural light and it cuts in half — from four hours to two hours a day — the amount of outdoor recreation to be provided detainees. In a review of a sample of 15 similar, publicly-available agreements between ICE and municipal or county governments — including facilities in Eloy, Arizona and Adelanto, California that have been heavily scrutinized over conditions — no similar waivers were found.

Whether the decreased hours of outdoor access are even provided is dubious, according to a local advocate.

“Someone could go days, or weeks even, without having access to the outdoors,” said Melissa Lopez, an immigration attorney who visits Otero regularly as the executive director of Diocesan Migrant and Refugee Services, an El Paso nonprofit serving the West Texas region.

“It doesn’t make sense to me,” Lopez said. “We’re in a part of the country where, for the majority of the year, we have really nice weather.”

Medical neglect, however, is Lopez’s main concern. Although the OIG’s report did not name Otero among the multiple facilities where inspectors found that care was lacking, Lopez says she’s heard complaints about health care from countless detainees during her 10 years of visiting four facilities across the region. Running trends, she said, include prescribing Tylenol as a treatment for serious ailments and the delay or denial of providing basic medicine, such as insulin or high blood pressure medication, for detainees with serious conditions that have long been diagnosed and treated.

“It’s not that the expectation is that somebody’s gonna get the best medical care on the market,” Lopez said. “We’re talking about basic care.”

Two of the 172 deaths in custody nationally between October 2003 and June 2017 that ICE has disclosed were at Otero. Fifty-year-old Rafael Barcenas-Padilla died most recently, of bronchopneumonia, in April 2016, according to ICE.

At the time, a scandal surrounding deaths in custody attributed to medical neglect was enveloping a different for-profit prison in northern New Mexico, the Cibola County Correctional Center. In the aftermath of investigative reporting that brought four deaths there to light, the prison’s corporate owner and operator, CoreCivic, faced an early contract termination with the Bureau of Prisons in the summer of 2016. But by fall, the private prison giant picked up $150 million in new business with ICE, and the facility was up and running as an immigrant detention center by the end of the year. The vendor now in charge of health care has been sued twice in New Mexico civil court for deaths due to medical neglect.

MTC, meanwhile, has been named as a defendant in New Mexico lawsuits around 30 times, according to a review of court records. A case brought by the ACLU on behalf of a transgender woman, who says she’s being held at the company’s state prison as a man, is currently being litigated. Recent settlements made by the company in New Mexico involve the alleged censorship of books sent to state inmates and a discriminatory firing complaint made by a guard at the ICE complex.

Legislative scrutiny

A deep dive from the Center for Investigative Reporting into Cibola’s closed door deal — and the unresolved questions of oversight and detainee care which surround it — has since prompted N.M. state Rep. Antonio “Moe” Maestas to set a legislative hearing on all federal facilities in the state to take place in the spring of 2018 via the Courts, Corrections and Justice Committee.

The deals — between Otero County and MTC, and Cibola County and CoreCivic — required the approval of the office of New Mexico’s attorney general. But state officials have been hands-off regarding involvement in matters of jurisdiction and oversight of federal prisons. Maestas thinks the dynamic is one that New Mexico’s leaders have a responsibility to remedy.

“Anything that happens in the boundaries of New Mexico, we should be concerned about,” Maestas said. The goal of the hearing, he said, is to “educate legislative members in regards to federal institutions here. We want to become familiar with their operations to ensure they’re run appropriately.”

“Anytime there’s no oversight or accountability, that’s when human rights violations are likely to take place,” Maestas said. “You never want your state to get a black eye in regards to being responsible for things of that nature.”

A 2011 report on conditions at Otero, compiled by the American Civil Liberties Union, could indicate that such a hearing is overdue. Two hundred Otero detainees detailed their experiences under MTC’s care with the ACLU. The resulting report featured a similar litany of violations as reported more recently by the Inspector General — from arbitrary lockdowns and abusive guards to deficient food and medical care.

The issue has never made it to the state Legislature, where it should be considered with urgency given the direction of federal immigration policy, Maestas said.

“Since the federal government is committed to a policy approaching mass deportation, there’s going to be more and more federal prisoners in the state. These are men, women and children, not street criminals convicted of federal crimes,” he said. “We need to keep an eye on what ICE and these companies are doing to ensure that it’s consistent with the values of our country.”

Even though the federal facilities aren’t managed by the state, Maestas said, “we still have to maintain high standards of human rights.”

Millions of dollars are at stake. A three month set of invoices paid to MTC, obtained by public records request, shed some light on the business of immigrant detention in southern New Mexico. MTC was paid between $1.8 million to $2.6 million per month between January and March 2017, as the Otero detainee population fluctuated between 914 and 741. The company charges Otero County, which is paid by ICE, $77 per detainee per day for the first 850 detainees, the invoices indicate.

On the horizon

Meanwhile, in the wake of a scandal in Texas involving the reopening of MTC’s notorious Willacy County facility, a new MTC ICE detention center on the horizon in Wyoming has stirred tensions over prison economy jobs and immigrants rights, says Antonio Serrano, a 32-year-old father of five from Cheyenne who is organizing, as chair of the statewide grassroots advocacy group Juntos, to halt the approval of MTC’s contract before it can start.

(c) Andrew Graham / WyoFile

Antonio Serrano

“With my knowledge of what happens in private prisons, they’re horrific. They do things so secretly, and I don’t want that in my state,” Serrano said.

Despite differences in politics and desperation for jobs, he has faith that his fellow residents can find an innovative way to spur their economy rather than rely on imprisonment.

“We have a lot of wind and a lot of sun and a lot of people who use to work in the energy industry,” he said. “I really think that with some retraining that a lot of those guys and those women could get these newer jobs.”

People in Wyoming are desperate for work, he said, and unaware of the human cost detention centers can pose.

“I’ve sat across the table from so many crying moms and crying wives, and been on the phone with a husband who lost his wife and he didn’t know what was going on, and I could hear the kids crying,” he said. “There’s so much happening that people don’t realize.”

Sarah Macaraeg is a reporter with the Asian American Journalists Association’s Criminal Justice Project.