Josh Bachman / Las Cruces Sun-News

Jonathan Firth, Virgin Galactic’s executive vice president for spaceport and program development, said the company needs some secrecy, especially for things like estimated flight schedules and technology development. But his response made clear that not all companies are demanding the level of secrecy that Spaceport America officials want in New Mexico.

The spaceport wants the ability to keep all sorts of information secret and is already shielding most companies’ rent payments from the public

You don’t have a right to know how much money companies that do business at Spaceport America pay to use the publicly owned facility, officials there say.

In fact, the spaceport wants the ability to keep all sorts of information secret, including the identities of commercial space companies doing business there.

The growing commercial space industry is hypercompetitive. Publicly releasing rent payments, lease agreements and other information harms the spaceport’s efforts to recruit companies, N.M. Spaceport Authority CEO Dan Hicks says – and that makes it more challenging to grow the spaceport and build a stronger economy in southern New Mexico.

“If you were to ask them would they want their leases out in the public they would say no,” Hicks said. “…We just don’t want to have additional burdens on them or scrutiny on them.”

That’s a controversial stance in a poor state that has invested more than $220 million in Spaceport America – a state whose law intends that the public be given access to “the greatest possible information regarding the affairs of government,” which it calls “an essential function of a representative government.”

There’s a real tension created by the public/private partnership that is the spaceport. On one hand, greater secrecy may help attract companies that demand it, and with them may come good-paying jobs the state needs. On the other hand is the principle that opening the spaceport’s finances builds accountability and public trust that is key to winning the government funding on which the spaceport also depends.

Senate President Pro Tem Mary Kay Papen, D-Las Cruces, sponsored legislation on behalf of the spaceport earlier this year that would have let the agency keep rent payments, trade secrets and other information secret. One committee approved the bill, but then it died.

These days Papen says she supports withholding company trade secrets from the public. But she no longer backs secrecy for money coming into the spaceport from private companies.

“If our Doña Ana County taxes are going for the upkeep and support for the spaceport, then I think how much private money we’re collecting certainly is within the realm of what the public should be able to know,” Papen said.

Leases released, but info blacked out

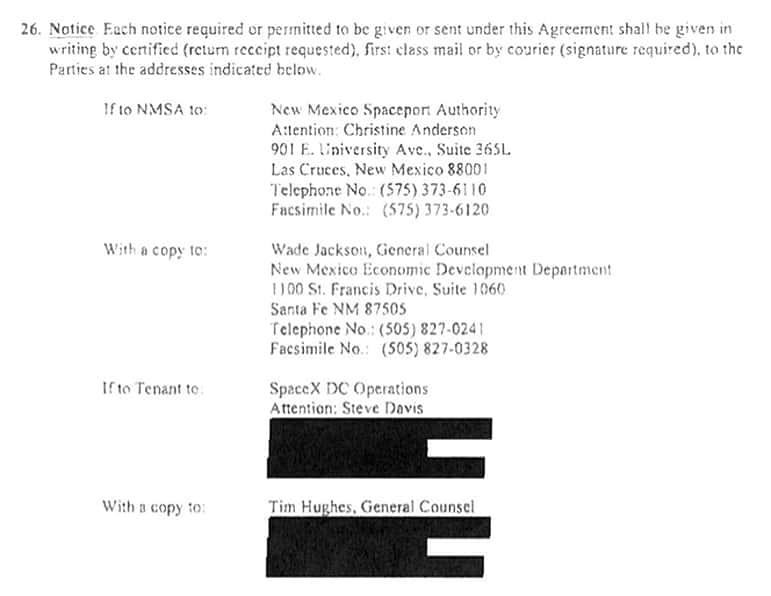

Though the agency unsuccessfully sought legislation earlier this year to protect rent payments from public disclosure, the spaceport now claims it already has that right. In response to a formal request under the state’s Inspection of Public Records Act (IPRA) from NMPolitics.net, the Spaceport Authority released lease agreements with five commercial space companies – Virgin Galactic, SpaceX, UP Aerospace, EXOS Aerospace and EnergeticX – but blacked out rent payment and other information in four of those leases.

As part of our months-long investigation of the spaceport, NMPolitics.net also requested all supporting documentation for a slideshow presentation that claims the spaceport generated $20 in economic activity for every $1 the state spent in fiscal year 2016. That should have included rent payments from private companies and other money that came into the spaceport’s bank accounts. There are no documents, the agency asserted.

NMPolitics.net’s aim in seeking the financial information was to share data that would help the public analyze the success of the decade-old project, which was intended to create new jobs and spark tourism.

So what did NMPolitics.net learn about the income the spaceport is earning from the five commercial space companies? Nothing the public didn’t already know. The slideshow highlighting the spaceport’s economic impact claims – the presentation the spaceport says has no supporting documents – states that Virgin Galactic’s direct spending in Fiscal Year 2016 was $3.3 million, and other companies combined to spend $1.3 million. But we weren’t given documents that would verify those numbers or provide details.

A previous Spaceport Authority administration released Virgin Galactic’s lease agreement to the public, so there was no point in redacting it in response to NMPolitics.net’s request, Hicks said. The 20-year lease with the spaceport’s “anchor” tenant shows what the public already knew: Virgin Galactic has been paying $1 million per year in rent for the first five years. There’s a formula in the lease agreement to calculate rent for the remaining 15 years, which officials say amounts to about $3 million per year starting in 2018. Additional fees are built into the lease as well.

NMPolitics.net didn’t get more information from the state agency responsible for complying with records requests – but Jonathan Firth, Virgin Galactic’s executive vice president for spaceport and program development, told NMPolitics.net the company has paid just over $7.1 million in rent and fees to the spaceport.

What about the other companies? The spaceport’s current administration is shielding how much they pay in rent and fees from the public.

Other information that was redacted in some or all of the leases with SpaceX, Up Aerospace, EXOS Aerospace and EnergeticX included sections that indicate where at Spaceport America companies are operating, insurance information – and, in the SpaceX lease, even the contact information for two company officials.

Spaceport America hasn’t always been so secretive. In addition to releasing Virgin Galactic’s lease without redactions before Hicks was in charge, the agency has also shared details about its agreement with SpaceX. Hicks’ predecessor, Christine Anderson, was quoted in 2013 as saying SpaceX would be paying $6,600 a month for three years to lease a mobile mission control facility and $25,000 per launch to test a reusable rocket.

In other words, today the spaceport is trying to keep secret information it released to the public four years ago that’s still available online.

Are the redactions legal?

To justify redacting portions of the lease agreements, the Spaceport Authority’s general counsel, Melissa Kemper Force, cited the provision in IPRA that allows withholding information “as otherwise provided by law,” then pointed to a New Mexico Supreme Court rule of evidence that states, “a person or entity owning a trade secret has a privilege to refuse to disclose, or to prevent others from disclosing, the trade secret.”

But do evidence rules for the judicial branch apply to an executive branch agency’s response to a records request? The rules state that they “govern proceedings in the courts of the State of New Mexico.”

Peter St. Cyr, executive director of the N.M. Foundation for Open Government, took issue with the redactions. The Spaceport Authority, after unsuccessfully seeking legislative approval to withhold certain information, is now acting as if the Legislature gave its approval, St. Cyr charged. He said the agency can’t “stubbornly withhold information on their own whim” and urged the release of all information NMPolitics.net has requested.

“They need to stop imposing their own secrecy rules and rely on the Legislature to determine what can be put in a bottom desk drawer under lock and key,” St. Cyr said.

Whether state law protects, or should protect, spaceport trade secrets isn’t the only question. The other is what constitutes a trade secret. Does it include rent payments?

Force cited the state’s Uniform Trade Secrets Act. It defines such secrets as “information, including a formula, pattern, compilation, program, device, method, technique or process” that “derives independent economic value” from being secret and “is the subject of efforts that are reasonable under the circumstances to maintain its secrecy.”

That law doesn’t mention rent payments. Papen said such payments “certainly shouldn’t be a trade secret.”

Sen. George Muñoz, D-Gallup, agreed. “There should be nothing secret about the income of the spaceport. It’s publicly financed,” he said. “Trade secrets I agree with – operations, negotiations shouldn’t be public – but lease agreements, once they’re signed, they’re public record.”

Lt. Gov. John Sanchez, a non-voting member of the spaceport’s governing board and chair of the national Aerospace States Association, also said rent payments should be public.

“Knowledge of the income the spaceport brings in is vital for the public to assess progress and viability,” the Republican said. “While many elements of the development of aerospace technology are proprietary, the financial viability of Spaceport America is the business of every New Mexican.”

No New Mexico officials interviewed for this article, other than spaceport employees, said the spaceport should be able to keep rent payments secret.

In at least two other states, officials believe they are allowed such secrecy. The state agency that runs Florida’s commercial space program can withhold rent information “if there’s a compelling reason,” asserted Dale Ketcham, Space Florida’s chief of strategic alliances. In some instances, Ketcham said, space companies don’t want competitors to know what they’re doing, and the amount of rent payments might provide clues.

But Barbara Petersen, president of the Florida First Amendment Foundation, doesn’t believe that state’s law protecting trade secrets applies to rent payments. “Any assertion that such information should be protected would undoubtedly be challenged in court,” Petersen said.

Virginia law allows secrecy surrounding space company trade secrets and information “relating to rate structures” if disclosure would “adversely affect the financial interest or bargaining position of the state agency.”

Megan Rhyne with the Virginia Coalition for Open Government said SpaceX “essentially said they wouldn’t come to Virginia without the exemption.” Rhyne said she isn’t sure the law in Virginia, home to the Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport, protects rent payments from public disclosure. But, she said, there’s “certainly an argument for it.”

‘It’s not all or nothing’

Because Hicks asserted that commercial space companies want such secrecy, NMPolitics.net asked New Mexico’s most high-profile space company, Virgin Galactic, to weigh in. Firth said the company needs some secrecy, especially for things like estimated flight schedules and technology development. But his response made clear that not all companies are demanding the level of secrecy SpaceX sought in Virginia.

Papen’s legislation would have allowed the spaceport to keep secret customer information including identity, correspondence, schedules, agreements, payments, activities, technology, visitor logs and policies. Virgin Galactic took no position on the legislation, Firth said.

“It’s not all or nothing,” he said. “There are some categories I’m sure would be more concerning than others.”

When asked whether Virgin Galactic would prefer to keep its rent payments secret, Firth didn’t directly answer. But he did share that the company has paid just over $7.1 million in rent and fees to the spaceport.

Still, Firth said he understood Spaceport America’s challenge when other states “can say to these customers, you don’t have to worry, you don’t have to release this information.”

“I can see their point,” Firth said. “But I don’t think that everything about everything needs to fall under that.”

The tension has Rep. Bill McCamley, D-Las Cruces, uncertain about what spaceport information should be available to the public in New Mexico. McCamley has been working for a decade on Spaceport America issues, both as a county commissioner and state lawmaker.

Because the spaceport is publicly funded, McCamley said he wants as much information as possible to be “known and public.” At the same time, he said, “companies value privacy so greatly that I do think we have to be careful, especially with things like research and trade secrets, that we protect their ability to experiment and not give away what they’re doing.”

Ketcham, the Space Florida official, said competition among commercial space companies is stiff. Secrecy allows the market to become even more cutthroat, he said – which will spur innovation and ultimately reduce the cost of human space travel. “And humanity is going to be well-served,” Ketcham said.

The redactions in the lease agreements the Spaceport Authority provided to NMPolitics.net were “designed to honor the rights that New Mexican state law provides to innovators, developers and entrepreneurs who seek to move their operations to our state and, hopefully, create jobs, boost the economy and help us become a leader in the space industry,” said Force, the agency’s attorney.

Papen, on the other hand, said the spaceport should release rent payment information if it wants the public to trust the project. She doesn’t plan to sponsor any legislation in the future to make rent payments secret.

“I think if they want to bring back the legislation… they’re going to have to revise that request that they have and make it so that it is tenable for everybody,” Papen said.

Hicks said the spaceport will continue to seek legislation to allow greater secrecy, including the protection of rent payments from public disclosure.

“If the industry didn’t need it then I wouldn’t push for it,” Hicks said. “There’s other companies out there that would not come and will not come unless we have the same protections that Virginia gives them.”

“I want to level the playing field and make their decision to come to New Mexico an easy, no-brainer decision,” Hicks said. “That’s my goal.”