Like a town dance or charity dinner, Judge Jeff Shannon’s visits to Peñasco were announced in black movable letters on a marquee in front of the community center.

Every other Friday, Shannon or the other magistrate judge in Taos County, Ernest Ortega, would drive through the mountains from their courthouse about 45 minutes to the north and hold court in Peñasco, an unincorporated community of nearly 600 people in the shadow of Jicarita Peak.

While hardly ceremonious, the community center was practical. The judges could use the copy machine for free, and the building was a gathering place. Locals sometimes played pool while the judges held court equipped with little more than a box of files and rubber stamps, handling traffic citations and other minor offenses, saving at least a few residents of southern Taos County a 60-mile round-trip drive into town along wending forest roads.

But Shannon and Ortega do not make the trip anymore.

Cash strapped and understaffed, the state’s court system has told them to stop holding court in Peñasco.

And this year, the New Mexico Legislature will vote whether to close two part-time magistrate circuit courts in similarly remote communities.

As the state’s judiciary looks for savings everywhere it can, judges such as Shannon worry the cuts could make the court system less accessible for rural New Mexicans, undermining a principle embodied by the circuit courts where the high-minded idea of equal justice under law meets the reality of life on the frontier.

In Taos and Catron counties, where circuit courts are scheduled to close, judges concede shuttering courts that are only open one day each week and do not have any dedicated staff is an obvious choice as the judiciary grapples with a budget shortfall.

But they also worry the closures will be an added hardship for rural residents.

If the Taos County Magistrate Court in the northern town of Questa is closed, for example, dealing with a speeding ticket will require at least a 100-mile round-trip drive for residents of communities near the border with Colorado, such as Amalia and Costilla.

“The assumption is that people can just drive. That assumption is misplaced,” said Shannon between traffic cases one morning last week. “Many people don’t have gas, money, cars.”

State law requires magistrate judges in some of the most sprawling counties to hold court in distant reaches of their jurisdiction, giving rural residents a chance to take care of legal matters without traveling to a faraway county seat.

And magistrate courts are where New Mexicans most commonly interact with the state’s justice system. The courts handle everything from speeding tickets to drunken-driving cases to disputes over relatively small sums of money. Magistrate judges are often the first to hear the evidence on felonies, too, before referring the cases to district courts. Giving such proceedings a People’s Court feel, magistrate judges in many parts of the state are laymen, not lawyers.

The state currently operates eight circuit courts.

But the House of Representatives voted overwhelmingly earlier this month to close the circuit courts in Questa, a village of about 1,700 people in northern Taos County, and in Quemado, a community of a couple of hundred people north of the Gila National Forest in Catron County.

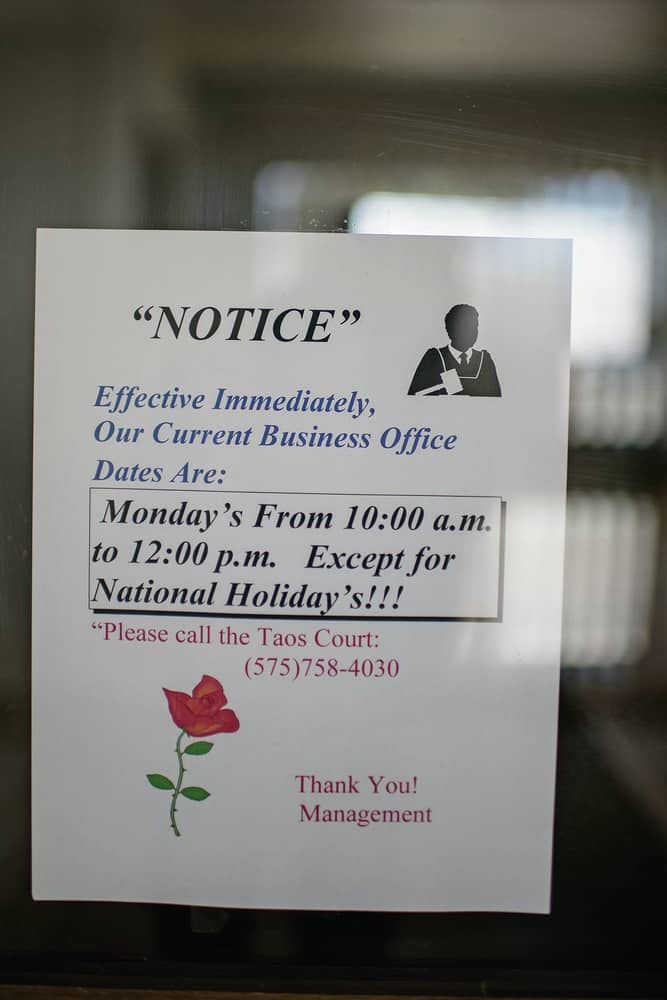

Neither court has its own staff. In Catron County, the only magistrate judge and his clerk make the trip to Quemado each Wednesday, while Shannon and Ortega take turns driving to Questa with a clerk from Taos every Monday. The biweekly, two-hour court sessions in Peñasco were not an official circuit court. The judges say they did not take staff with them or ask to be reimbursed for the drive.

The circuit courts operate out of rented space, and legislative staffers estimate that closing the facilities altogether could save the state a total of $26,000 each year.

The biggest savings, according to the analysis, come from the increased efficiency of keeping judges and clerks in court rather than dispatching them to another town for a day.

Fifteen percent of jobs in the state’s magistrate court system are vacant, and requiring employees to travel further strains an already short-staffed judiciary, the committee’s staff wrote.

That is evidence enough of the budget crisis facing courts around the state, Ortega said.

“The Administrative Office of the Courts is having to choose between keeping circuit courts open and furloughing staff,” he said.

The Legislature is considering closing the two circuit courts just a few months after it voted in the fall’s special session to cut more than $800,000 from the budget for the state courts because the judiciary was already grappling with a financial shortfall.

“I wouldn’t like it, either, if I was 40 miles from the nearest courthouse,” said Arthur Pepin, the judiciary’s top administrator as director of the Administrative Office of the Courts. “But it’s hard for me to justify using several thousand dollars for a courthouse that is so rarely used.”

Legislators voted to close four circuit courts during the state’s last budget crunch in 2009.

And in this latest round, the courts under the knife have seen falling caseloads.

In 2016, 267 criminal cases were opened in the Questa court, a drop from 312 in 2015 and 526 in 2014. The number of cases in the Quemado court has similarly shriveled from a recent high of 355 in 2010 to 14 in 2016.

The numbers tell only part of the story, however, because both courts have also lost staff in recent years and moved the filing of many cases to the county seats in Taos and Reserve.

“We were plenty busy,” Judge Clayton Atwood said of the Quemado Magistrate Court.

Atwood has spent the past 14 years presiding over what he describes as a little piece of heaven in Western New Mexico — the state’s largest county and one of its least populated, covered in forest and mountains.

Like elsewhere in New Mexico, though, drugs are a problem, Atwood said.

Atwood refers to the court as providing judicial outreach — offering services to local residents where they live and making the court system a little easier to use.

But the circuit court no longer has a clerk and is no longer open three days a week.

Now, the court will close altogether, leaving residents on the county’s north end with a two-hour round-trip drive to the nearest magistrate court.

“I don’t like it,” Atwood said. “But I understand it.”

Asked if the hassle of going to court should just be considered part of getting a speeding ticket, Shannon is quick to rebut that everyone — even in traffic cases — is innocent until proven guilty.

“There should be as little hassle as possible to get due process,” he said, before returning to the bench for another traffic case.

Contact Andrew Oxford at (505) 986-3093 or aoxford@sfnewmexican.com. Follow him on Twitter @andrewboxford.