COMMENTARY: My first day teaching at the University of Wisconsin-Madison was an eye-opener. Following my Ph.D. I was asked to stay and teach in the Department of Educational Policy Studies.

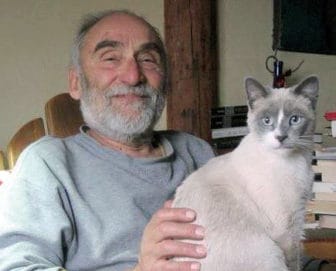

Courtesy photo

Emanuele Corso

Of course I was thrilled and, at the same time, thoroughly intimidated. On the first day I picked up the enrollment roster at the department office and, although I was half an hour early, I went to the assigned classroom, which was empty. I took a seat somewhat in the middle of the room and imagined myself at the lectern.

What was I going to say? I had plenty of experience, having taught for the university’s extension service for several years, but this was different. My Ph.D. was in adult education. Well, I concluded, students are adults, so what’s the problem?

Soon after taking my seat the bell rang, the corridors were filled, and students began to arrive. I remained in my seat in the middle of the room as students took their seats. I was amazed that the room was nearly filled and my anxiety level rose in proportion. Pretty soon things quieted down and the expectant group sat facing the front of the room. Eventually the 10-minute bell rang indicating that if the professor had not arrived students were free to leave. A few gathered their belongings and made for the door.

“Whoa, hold it!” I said while remaining in my seat. “Where are you going?”

“The prof isn’t here, we’re leaving.”

“How do you know the professor isn’t here?”

The student pointed to the empty desk. “He isn’t here.”

“Are you telling me your expectation is that teachers are always to be found at the front of the room?”

At this point suspicions were aroused, my cover was blown, I introduced myself, and thus began my teaching career seated in the middle of the room. For me and for the students this was the beginning of the dialectic that defined our time together, that defined my teaching.

Teachers are not always at the front of the room. Teachers can be anywhere. Yes, the front of the room carries the weight of established authority, but what kind of authority? Is a teacher’s authority defined by where they are standing or by what they know and by what they are capable of getting across? If a teacher’s authority is defined by anything other than what they know and are capable of communicating, what is being taught? What is being learned?

Teachers must, I believe, ask themselves these questions every time they enter a classroom. I did, and I reminded myself of it constantly. How could I teach what I didn’t practice, especially when my students were future teachers?

Schools are an extension of society, and that alone establishes their value and importance. If this were not true, totalitarian governments would not exercise such control as they do over teachers and students. Public education is, of necessity, as much about social control as it is about subject matter. Social control at an early age is preparation for a lifetime of respect for authentic authority and responsible membership in society.

Children must be educated to be fully functioning members of society, a process that is thousands of years old. And how does this happen when children’s noses are pressed against computer screens informing only themselves in a circumscribed and contrived personal world?

It won’t happen, because “public” means all of us, including children, working and learning as a community, not as self-enclosed, hermetic, self-absorbed centers of private experience. Public is the antithesis of self-centeredness. Public means all of us working together, learning and teaching, not grasping whatever we can at whatever cost to the community, oblivious to an inclusive social contract.

The foundational conception of public education is neither capitalism or socialism. It is not about Republicans or Democrats, not about profit, but about civility, about community, about democracy.

How can this be taught? Not from the front of the room, that’s for sure. Lau Tzu instructed us to lead from behind.

Emanuele Corso’s essays on politics, education, and the social contract have been published at NMPolitics.net, Light of New Mexico, Grassroots Press, World News Trust, Nation of Change, New Mexico Mercury and his own — siteseven.net. He taught Schools and Society at the University of Wisconsin-Madison where he took his PhD. His bachelor’s was in mathematics. He is a veteran of the U.S. Air Force’s Strategic Air Command, where he served as a combat crew officer during the Cuban Missile Crisis. He has been a member of the Carpenters and Joiners labor union, Local 314. He is presently working on a book: Belief Systems and the Social Contract. He can be reached at ecorso@earthlink.net.