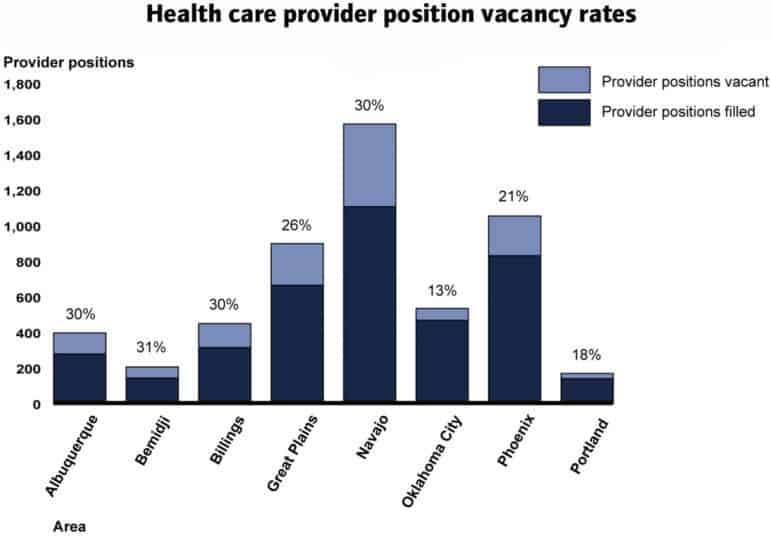

Almost a quarter of all positions for physicians, nurses and other care providers at Indian Health Service (IHS) facilities are vacant in most service regions, according to a report published in August by the Government Accountability Office, or GAO. This prevents the agency from providing “quality and timely” health care to tribal citizens.

Source: GAO analysis of November 2017 IHS data

In half of IHS’s coverage areas, a third of health care provider positions sit vacant.

Established in 1955 to provide direct care to enrolled members of 573 federally recognized tribes, IHS operates a network of 55 health centers, 26 hospitals and 21 health stations, primarily in rural areas. In 2016, those facilities received 5.2 million outpatient visits and admitted more than 15,000 inpatients. In 2016, approximately $1.9 billion was allocated to fund these services.

The GAO report looked at eight geographical areas and found that between 13 and 31 percent of provider positions were currently vacant. Many patients receive curtailed services as a result. “One doctor we spoke with,” read the report, “described this dynamic of vacancies begetting additional vacancies as a ‘never-ending cycle.’ ”

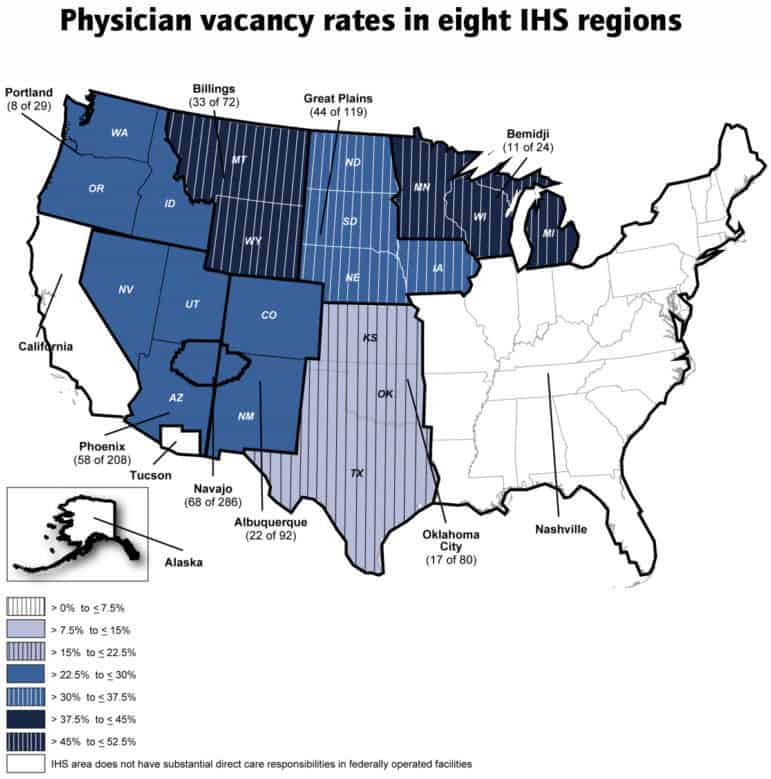

Physician vacancy rates are even higher, with some regions filling only half of their desired positions.

Many IHS facilities, often in rural areas and on reservations, are considered “isolated hardship” sites, designated as “unusually difficult” posts for providers. The problem frequently stems from an inability to provide market salaries or housing for providers. Even incentive programs, like student loan repayment in exchange for service contracts, lack funding. In the Billings area, for instance, five physicians left IHS in a two-week period after they failed to receive loan repayments. Many facilities must rely on short-term employees, even though the practice is often more costly than hiring full-time staff.

Some clinics and hospitals have had to cut services. At the Nevada Skies Youth Wellness Center, a substance abuse treatment facility for adolescents, staff shortages led to a decrease in the number of beds available. At a hospital in Rosebud, South Dakota, OB/GYN patients have been diverted to facilities 45 miles away since 2016.

And Chlamydia tests at the San Sioux Hospital, also in South Dakota, had to be sent to other laboratories, sometimes delaying treatment for over a week. In 2016, the National Congress of American Indians estimated that IHS allocates $2,849 per patient, compared to $7,717 per person for health-care spending nationally.

The GAO report recommends that the IHS director obtain more information on temporary employee contracts to make better decisions on the budget.

The government-to-government relationship between tribes and the United States sets the legal basis for providing American Indian and Alaska Natives with health care. In exchange for land cessions, the federal government promised to provide assistance for Indigenous people, including medical services.

This article originally appeared on High Country News, a nonprofit news organization that covers the important issues that define the American West. Subscribe, get the enewsletter, and follow HCN on Facebook and Twitter.

Elena Saavedra Buckley is an editorial intern at High Country News. Email her at elenasb@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor.