Courtesy photo

Families and Youth Inc. has been approved to provide Medicaid-funded behavioral health services and is going through the process of getting approved by the state’s insurers. The process will likely take several more months, FYI’s CEO Brian Kavanaugh says.

Even in his final days of battling leukemia in early 2016, Jose Frietze was fighting for the youth services agency he founded in 1977.

The state Human Services Department had accused the organization — Las Cruces-based Families and Youth Inc. — of potential Medicaid fraud and overbilling by $856,745 in 2013. A stop payment of $1.5 million in Medicaid funding for services already provided crimped FYI’s cash flow, leading to layoffs. And because of the accusations, FYI was forced to hand off part of its business to an Arizona company brought in by Gov. Susana Martinez’s administration.

Frietze’s daughters Victoria and Marisa remember how tough the allegations were on Frietze and their family.

“We were there when they first started off,” Victoria says. “When they had a small building, when they got the new building, when they moved up. I mean, we’ve been there all our lives, with him, and to see everything that he worked for just …”

“… fall apart …” Marisa interjects softly.

“It was heartbreaking,” Victoria says.

Marisa and Victoria are gathered around the family’s kitchen table with their mother, Vivian, to quietly, but ardently, defend the man Marisa calls “our everything.”

Despite the suspicions and bad headlines, Frietze, a former longtime Las Cruces city councilor and school board member, remained confident until the day he died that FYI would be vindicated, they say.

He was right. A month before he died on March 2, 2016, the state Attorney General exonerated FYI. All 15 behavioral health organizations accused of Medicaid fraud by the Martinez administration in 2013 would eventually be cleared.

Perhaps Jose Frietze was so confident because in 2012 FYI had gone through an investigation by the state Attorney General’s Medicaid Fraud Control Unit after the organization discovered and self-reported billing problems. That investigation covered three-quarters of the period that just months later would be audited by a consultant for the state. And, FYI had in hand an agreement that released it from any liability, civil or criminal, for the period of November 2009 through May 2012.

In August 2016, HSD notified FYI it had found the agreement. A month after that, HSD released FYI’s frozen Medicaid funds and dropped its overbilling allegations.

“It appeared like, oops, time to release their payment,” says Brian Kavanaugh, who succeeded Frietze as FYI’s CEO.

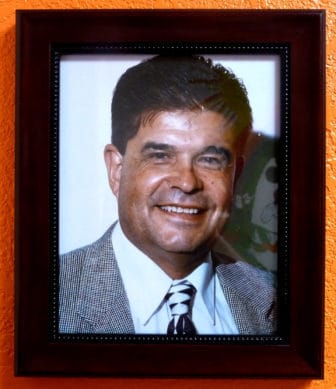

Courtesy photo

A portrait of Jose Frietze hangs in the family home. It is the favorite of his wife of 41 years, Vivian.

The Human Services Department did not respond to NMID’s questions about the settlement agreement and the reasons why it dropped overbilling charges and released the Medicaid dollars.

Their silence leaves unanswered questions: Why did HSD target FYI as one of the 15 organizations to be audited in 2013? Did HSD mistakenly target FYI in 2013?

If HSD was in regular communication with the Attorney General’s Office in the lead up to the 2013 audit of 15 organizations, including FYI, as state documents show, did the human services agency know of the 2012 agreement?

If it did, why did it continue to demand reimbursements for overbilling over the full period covered by the 2013 audit — July 2009 through January 2013 — instead of just the time not covered by the 2012 agreement?

Kavanaugh, who has been with FYI for 14 years, believes HSD knew about the agreement. FYI provided copies multiple times, but it never got a response, he says.

Roque Garcia, CEO of Southwest Counseling Center, another accused organization, remembers Frietze hand-delivering the agreement to an HSD official in Santa Fe after the 2013 audit.

“It was at the capitol when we saw Larry Heyeck,” Garcia said of then deputy general counsel for the Human Services Department. “I told Larry Heyeck, ‘FYI has already been audited and there has been an agreement that has already been given. You can read it.’ ”

Unlike FYI, Garcia’s Las Cruces organization didn’t survive the state’s accusations, even though it was exonerated like all the rest. In May, after the years of battling overbilling estimates that reached $2.8 million as recently as January, the state reduced to $484.71 what it said Southwest Counseling Center owed, which the organization paid.

To Kavanaugh’s knowledge, the Human Services Department never acknowledged whether it had received the agreement from FYI. And it never told them why it was dropping demands for repayment.

Fighting until the day he died

Jose Frietze spent most of his adult life dedicated to helping children in Las Cruces and serving his community — he served a combined 22 years on the local school board and city council.

When he died there was an outpouring of remembrances in Las Cruces.

Vivian, his wife, says the dismantling of FYI hurt Frietze and the many people working there, but even more so because of the collateral damage. “There was no place to go for some of those children.”

And, Frietze was determined to bring a lot of services back to children and youth in southern New Mexico. “Even a few hours before he passed away, he was still talking about FYI, his plans,” says Vivian, a petite woman with short-cropped dark hair wearing silver and turquoise earrings.

These days, FYI is rebuilding.

Kavanaugh says the agency has been approved by the state to begin providing Medicaid-funded services again. It will be a long process. FYI still can’t be reimbursed by the state’s managed care organizations. First, FYI must be credentialed by them, then they need to negotiate contracts. Hopefully, says Kavanaugh, that will happen within the coming months.

While that process continues, FYI is looking into just what services to bring back. In May, La Clinica de Familia closed a youth shelter and group homes for teens.

“We ran those homes successfully for over 20 years,” Kavanaugh says. “And in the space of three and a half years, they went to La Frontera, then La Clinica, and now they’re closed.”

La Frontera New Mexico is the Arizona company that took over FYI’s business but departed New Mexico in 2015.

Now FYI is looking into reopening the homes, and is talking with the state Children, Youth and Families Department, as well as other stakeholders, Kavanaugh says. “We’re trying to fill the gaps in service that we have in southern New Mexico,” he says.

It is the slow, steady revival Jose Frietze had been hoping and planning for, but will not get to see.

Frietze’s daughter, Victoria, recalls her father’s optimism about rebuilding FYI.

“He knew they were gonna get cleared, he knew they were gonna get money, cause he was there 24/7 working on it,” says Victoria. “He just knew it was gonna take some time, but he envisioned them getting programs back, building up, even growing in the future. That’s what he saw happening.”