COMMENTARY: When was the last time someone told you that New Mexicans are a rich people?

Courtesy photo

Gabe Vasquez

Likely, never.

But we are.

As we each find meaning in Hispanic Heritage Month through our own experiences and perceptions, I can’t help but think of the conversation that often plays in my head as I drive around Las Cruces.

“We are a rich people.”

In Southern New Mexico, we are blessed with a rich and diverse tapestry of history, culture and tradition that comes to life in the people and landscapes we call home.

We are all owners — and keepers — of this unique and rugged place. A place that’s home to our families and our collective history.

It’s with the backdrop of our public lands and the jagged, sun-kissed peaks of the Organ Mountains that many important parts of Hispanic history — as well as our nation’s history — have been written here.

Gabe Vasquez

The jagged peaks of the Organ Mountains protrude from the Chihuahuan Desert, the proud home of one our of nation’s newest national monuments.

Hispanic Heritage Month is an opportunity for me to reflect on the people and the culture of Las Cruces and Southern New Mexico.

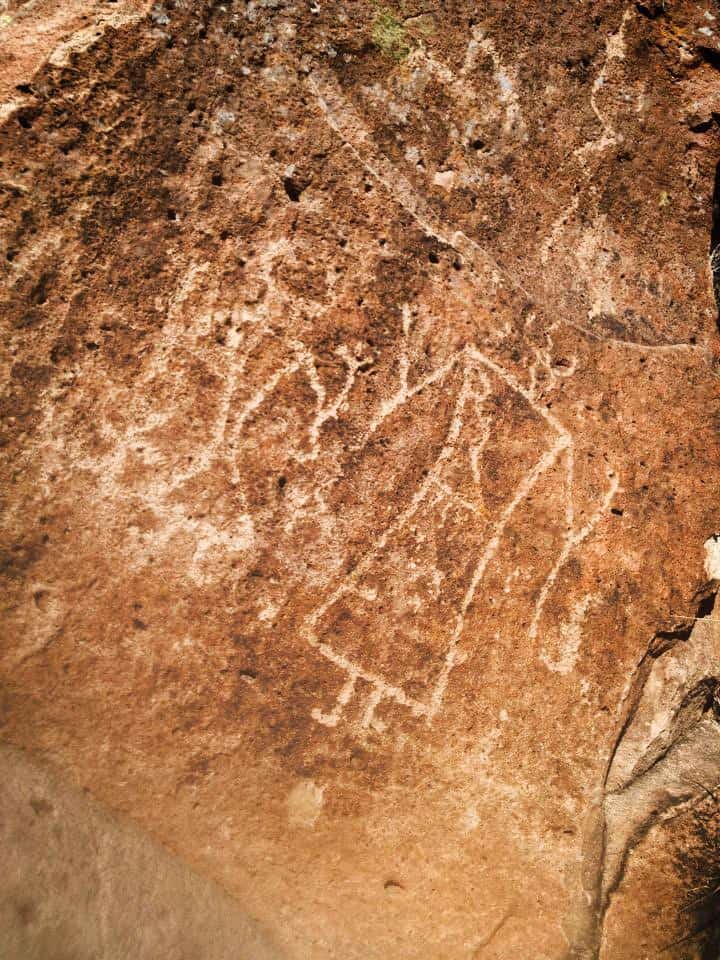

On a breezy October afternoon as I drive down Picacho Avenue near La Llorona Park, I think of the ancient Mogollon culture, which more than 1,000 years ago followed and hunted herds of deer and antelope and set up camps along the banks of the Rio Grande. Their history, culture and artifacts come to life in places such as the Gila Wilderness, the Mimbres River Valley near Deming, Castner Range in El Paso, Paquime Tanks in Chihuahua, Hueco Tanks east of El Paso, and in our own backyard throughout the Organ Mountains Desert Peaks National Monument.

Gabe Vasquez

A Mogollon-era petroglyph depicts two human figures with antlers at a cultural site in Valles Canyon, 20 miles west of Las Cruces in the Organ Mountains Desert Peaks National Monument.

I hop on Interstate 10 and head to El Paso to visit my family, and I think of what life on the border was like in the 1700s. During this time, the Native Manso people first encountered Spanish settlers in what is now present-day Ciudad Juárez. I stop to take in the cool breeze and retrace the steps of the Manso on the foothills of the Franklin Mountains. I think of the proliferation of the American Mestizo during this time as the Spanish and Native cultures mixed and new families settled the Rio Grande corridor and Camino Real de Tierra Adentro. Many of these families have remained here for generations.

I drive further into El Paso and see the stark contrast between my two home cities, cities that share the same land, history, and lineage but are divided by a border fence. I can’t help but think of the tremendous impact of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the Gadsden Purchase. Two agreements that have recently divided the land and the people, despite them having been united for thousands of years.

On my way back home, I take the scenic route back to Las Cruces on Highway 28 through the Town of Mesilla and stop to look at the Mexican national and New Mexican state flags both proudly emblazoned in the heart of the plaza. I think of the first 33 Mexican settlers who founded the Doña Ana Bend Colony, the first Mexican settlement in the Mesilla Valley, back when New Mexico was still under Mexico’s rule.

I drive out of Mesilla and see a road sign pointing me in the direction of Deming. I think of a time when Pancho Villa could be seen from the peaks of the beautiful Tres Hermanas Mountains leading the Villistas on a full-scale assault of the 13th Calvary Regiment near modern day Columbus. I also think, “The Tres Hermanas is a fitting name for this range, but what might have the Native settlers called these mountains?”

Gabe Vasquez

The Tres Hermanas Mountains sit in the Chihuhuan Desert less than 10 miles from the 1916 Battle of Columbus.

These, and so many other rich stories of our Hispanic Heritage, come to life on our protected public lands in and around Southern New Mexico. Our Hispanic heritage lives and breathes in these special places — places that exist for our recreation, reflection and enjoyment.

Hispanic Heritage Month also prompts me to think of the potential for this all to disappear in the next generation if we don’t fight for and protect what we have in our own backyard.

There is a very real threat across the West led by the rich and powerful, a movement led by special interests and supported by our own Congressman Steve Pearce, that seeks to transfer these special lands to state control to eventually be sold off to the highest bidder, limiting and potentially eliminating our public access to these beautiful places. Public lands are the nation’s equalizer — rich or poor, we should all have access to these treasures.

Here, this movement has already robbed Hispanic communities of their access to these places. Governor Susana Martinez shamefully recently signed into a law a measure that keeps New Mexican fishermen from having access to many public waters, limiting the enjoyment of our own streams and rivers to the rich and powerful. This bill was strongly supported by a Texas businessman who recently bought up thousands of acres in New Mexico.

Our public lands are under attack from rich, private interests across the West. We must fight to keep them in the public’s hands so that someday our grandchildren can set foot in them and retrace our footsteps. We must preserve the land where our families and ancestors have lived and thrived — now, and for future generations. Our Hispanic Heritage in Southern New Mexico depends on it.

Gabe Vasquez is the Southern New Mexico outreach coordinator for the New Mexico Wildlife Federation, an organization dedicated to the conservation of New Mexico’s public lands. He is a first-generation American and his family lives across the border region in Ciudad Juárez, El Paso, and Las Cruces.